I absolutely love restrictions in underwater caves. They offer a very different bodily experience from restrictions in dry caves, and play a multi-faceted emotional, mental, and physical role in a dive. The challenge of navigating a confined space without the pull of gravity is creatively liberating. The feeling of being pressed between the rock walls of Earth’s water-filled veins evokes a profound awareness: “I am beneath multiple atmospheres of pressure, I am navigating the depths of the Earth, and I am breathing.” Breath, in this state, is extra special.

These ideas—breath, restrictions, and breathing in a confined space underwater—are the topics of this post.

First Breaths

Breathing underwater is a wild experience. I have a vivid memory of my first breath as an open water student in 2012. I stood in the shallow end of my university’s pool with a single tank on my back. I put the regulator in my mouth and squatted so that my head would go under. I saw water–like I had a thousand times before, wearing goggles while swimming. Except this time, against my instincts, I had to draw a long breath. For just a moment I hesitated and paused. Then I inhaled.

I don’t know what I was expecting but this wasn’t it. The underwater world was quiet and my inhale made a loud whooshing noise, like air escaping from a pressure valve. I had to really pull the air into my lungs, as it didn’t come as easily as on land. Then I exhaled and the bubbles released from my regulator sounded thunderous. I quickly stood up so that my head and chest were out of the water.

Over the years the sound of breathing became natural. Underwater, the primary sound is one’s own breath. But to say these sounds became natural isn’t to suggest they fell into the background. Instead, they became the sound of SCUBA–they became instruments to understand the positioning of myself in space, sometimes more so than sight. Even in zero visibility, long whooshing inhales mean the body is slowly lifting up, while a quick, punchy exhale drops the body down. In a cave, the sound of breathing carries another complex layer of meaning, not only about the state of one’s body in space. Exhaled air becomes temporarily trapped along the curvatures and indents of the ceiling, and trickles out loudly like the cascading sound of a rainstick. The sounds indicate the presence of life and the passage of time.

Restrictions

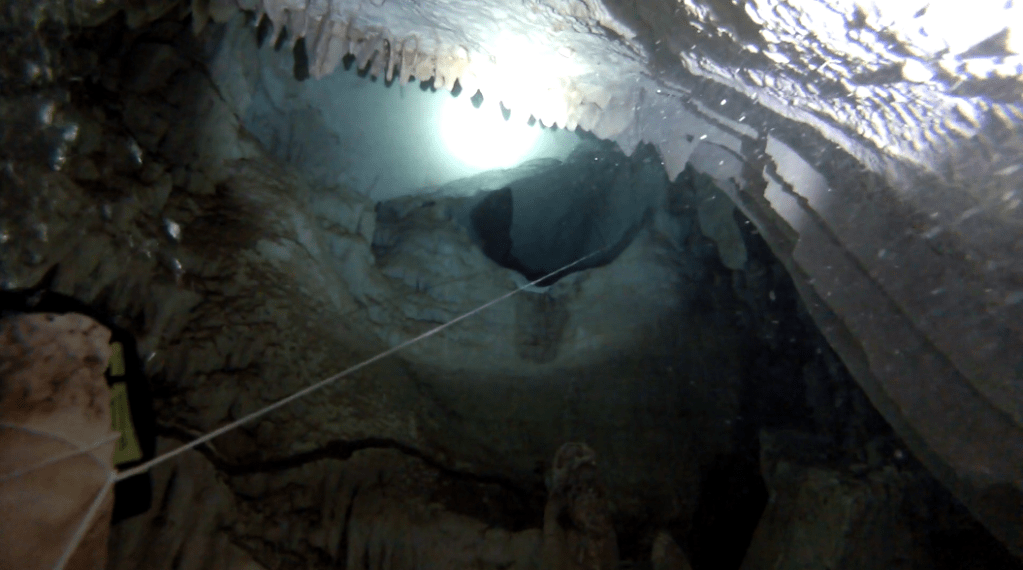

Before diving into the experience of breathing in a confined space, I will first define a “restriction.” Restrictions are tight passages in a cave that literally restrict the diver’s movement. The Caribbean, as one example, is known for winding, labyrinthine caves in which a single room might have many narrow tangents that lead deeper into the Earth. Restrictions might follow a relatively straight passage, or they might bend at rigid angles, blocking a flash light’s beam and the diver’s view.

During a cave dive much attention is focused outwards as the diver absorbs environmental cues or scans for potential dangers. This is often the case in large passages or decorated rooms. Restrictions, on the other hand, slow the cadence of the dive while limiting the diver’s movement and sight.

Carved within the Earth, restrictions each have their own unique shape. To pass through, the diver–squeezed beneath the Earth’s surface–must discover and interpret the shape of the restriction. With the head tilted and wedged between rock, it is not possible to see the formations behind the body, actively pressed against the body, or the passage that lies ahead. For these reasons, navigating a restriction relies on “feeling” rather than “seeing” as the diver senses the different pressures holding the body in place and experiments, moving hands forwards, to the sides, to figure out where the body fits next.

Lying in a restrictions brings attention back to the self as the diver negotiates bodily compression with the cave’s shape. With the arms in front of the diver, a pull forward might be followed by a shift backwards, or to the side. Using the arms to pull the body forward might be essential for freeing the torso or legs from the Earth’s hold. In doing this, the diver must observe the current moment–under ninety feet of rock and three atmospheres of pressure–relax the self, and allow these pressures to fall behind.

Breathing in a Restriction

Restrictions bring attention to the pressures compressing the body, and also to one’s breath.

“Only you can breath for yourself” is a quote commonly associated with the world of technical diving. Of course this is typically true in any case, such as on land. But here this truism emphasizes that SCUBA is an revolves around breath management. The active effort towards maintaining one’s own breath is at the core of all forms of SCUBA as divers must actively seek breath, plan their dive around breath, and ultimately bring a finite amount of air to sustain the self before returning to the surface. This ability to breath underwater is the factor that enables underwater exploration. The act of doing the breathing is the what limits the time spent underwater. This truism is especially pronounced in overhead environments, where there is no direct, vertical access to the surface. The quote, “only you can breath for yourself,” thus emphasizes the self-sufficiency of cave diving.

Breath has a particular feel in a cave dive.

translate emotions into tools

Bubbles Escaping

The end of a cave dive is loud as the ceiling of the cave collects exhaled air, so many bubbles trickle out to accompany one’s own breathing.

Reflections on Breathing and Restrictions, by the Second Author.

The second author does not remember his first breath underwater. He recounts: I’ve played hundreds of hours of silent Marco Polo in order to swim breathlessly and silently for minutes at a time. Why would I need all this gear, weight, and faff? But alas I must have taken my first breath anyway–in and out–and it made no strong impression.

On passing through restrictions: I remember it like it was yesterday. We were in training and the instructor pointed us to a very tiny hole in the corner, gesturing that we needed to go there–follow him there. And I remember that the restriction wasn’t so tight that you had to drag your way through — if you were doing things right you could float through without bumping walls. But then it angled right, and all of a sudden it’s getting tighter — the tank hits the top and there’s really no way to avoid it. But then we come out into a bigger room. Easy. The instructor rose up and then seemingly disappeared into another wall as if he phased through it. So we went to investigate, and the real restriction presented itself. We are two restrictions in at this point — the hole seems impossibly small. there’s no going back now. So we enter. And now both my tanks and my belly are sliding. And there’s not quite space for the legs and my pelvis is bent at a weird angle and all I can do is grab on to the rock in front of me and drag myself forward all the my legs helplessly flailing out the back of the hole, I’m sure hilariously for anyone behind me. And so bit by bit I drag myself through the hole, but not too fast in case I bump my extremely bony body against the extremely bony cave, a lesson I continue to learn every time I go diving. And just as fast as I’ve entered (which is real slow) the tank releases from the rocks on top of me, my legs slither out from the hole behind me, and I’m free. And then I think to myself: that was fine.

Photo Appendix