The pool of the cenote is a blue oasis. Unlike the rolling energy of the ocean, the water here is still and calm. It is a quiet and welcome reprieve from the buzzing and the heat of the jungle. The water heals our itchy, sweltering skin.

With our heads above the surface, the rubber hoses across the back of my neck still restrict me, but I can turn my whole body to look at my dive partners. We float here, together, then we each deploy our long hoses–long enough to donate air to another diver in an emergency. This procedure is to ensure our long hose hasn’t been obstructed, or pinned against our bodies–that the air we bring in a cave is accessible. I pull my regulator outwards, yank forward the hose, and once I see it is loose and free, I awkwardly pull the hose back into its original position.

We begin to let the air out of our BCDs. Cool water rises to my chin and I pause to take a deep breath from my regulator. With my regulator bobbing between the surface and the water, my breath sounds hollow but also bubbly. I’m careful not to release air from my BCD too quickly. My gear weighs around 90 pounds. With two tanks and a metal back plate, the water quickly gives way to my body as if pulling me under. The water rises up to my mask, now past it, and I take another deep breath. I see bubbles passing over my field of vision. My head is below the surface and the sound of jungle insects has been replaced with the total silence of an underwater world.

At depth we are floating, neutrally buoyant. The sun shines through the water onto a rock surface, and across bright green hydrophilic plants stemming from the Earth’s crevices. Like us, the leaves of the plants float and bob, as if unaffected by gravity. We each turn towards one-another and make eye contact. Against our black masks and black wet suites our eyes stand out, bright white. In the cenote pool we communicate with our eyes . . . they reveal ourselves without the need for voice or words. “I am good, are you good?” we ask one-another.

Entering the Mouth of the Cavern Zone

Turning towards the mouth of the cenote reveals a shadowy wall of darkness. We will leave behind the sun loving hydrophilic plants, the wavering distortions of green jungle trees visible through the water’s surface, to venture into a dark void that eats the beams of light shinning from our canisters.

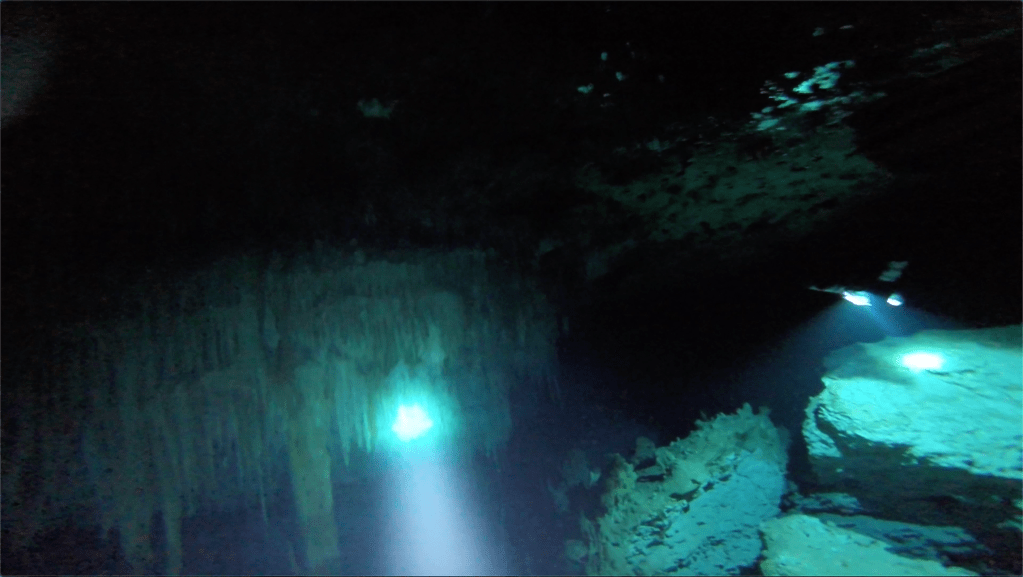

It is quiet underwater, and as we kick forward it becomes darker. Once we pass into the overhead environment we enter a sort of twilight zone. Stray beams of light from the surface can reaches us here, but it is dark and growing dimmer. This causes the rocks to take on a different appearance. The rocks directly before us shine a luminous white under our canister lights. Beyond these rocks, the whole room is filled with a blue gradient that spans in every direction. Large columns, painted a subterranean blue, reach from the ceiling to the floor. Everything beyond the columns is hidden in darkness, as if these columns were the entry of a portal to another dimension. These natural formations mark the transition between the cavern zone and the cave, where no light from the sun can reach.

Entering the Cave

Underwater caves impose sensory deprivation. The silence of the dive is now met with total darkness, only to be lit by the beams of our canister lights. We are floating here, unopposed by the force of gravity. My once rigid body–braced with hoses, clasped into a harness, tied with bungee to aluminum tanks–feels free. My tanks, once weighing me down while I trudged through the jungle, are floating next to me.

This physical freedom is met with restrictions imposed by the tenants of cave diving. Here, floating in this lawless space, our black masks block stray light from our canisters and funnel our sight forward. We move ahead in a single fashioned line, in an order we will retain for the entire dive into the cave, and in reverse for the entire dive out. Instead of looking into my partners’ eyes, I will note the intensity of his light and in what direction it shines. This is how he will communicate with me throughout most of the dive.

Muted, deafened, and carrying narrow beams of light, we develop a heavy sense of awareness of our environment and each other. I sense my dive partner across multiple dimensions of my own body. If he is in front of me and we are in a small, confined space then the pulse from his kicks pushes back on me. We dance together as I balance on water rifts that are shaped by his movements. If he is behind me, I understand the state of his body through the directionality, sway and tapering of his light. Using his light he casts his own presence forward, signaling “okay,” “attention,” “look at this,” to me as I face ahead. I can feel how close he is and how fast he is moving, and I may adjust my own kicks accordingly.

The rocks on the floor–once bathed in light–cast miniature shadows against one another as the beam from our canister light passes over. We have entered a room with unknown dimensions. Some rooms inside the Earth are so large that a beam of light cannot reach the other side. Instead, while floating in this space, the light disappears, seemingly into a vacuum. In this room, panning our lights reveals a space that is large enough to be comfortable, but small enough so that shinning our light in any direction reveals stalagmites, stalactites, and cave wall. Anything beneath the focus of our lights pops out, vividly, while the formations beyond the parameters of our beams appear dim and two dimensional before tapering off into darkness.

We kick forward, shining our lights to reveal more formations as well as dark recesses that lead down different passages.

Narrow Tunnels to Large Rooms

Cave topology is vast, and many journeys exist within a single cave. As we dive, the cave itself changes. Continuing forward into a new area of the cave, the rocky floor becomes smooth and flat. It is covered by a fine, powdery grey silt. The ceiling of the cave lowers. While moving through this narrow passage I gently kick above my rigid, flat body so not to disturb the silt. This would could cause a black-out and blind us.

Like the cave, our own bodies change. Consuming air causes our tanks to become lighter. They require adjustment to remain trim against our bodies and not angle towards the ceiling. As we traveled further we also went deeper. In this passage we are under two and a half additional atmospheres of pressure, and more air is needed in my BCD to stay neutral and not sink. My neoprene has become more compressed, and while the continuous kicking has kept my core warm, my skin still feels chill. We carefully glide, smooth and trim, over the silt.

Eventually, the narrow passage opens up and drops off into a large, dark room. I am taken by it’s vastness. Jumbo jets could be parked in here. We pass over a heap of boulders, some the size of a bus. Peering between the boulders reveals more passages and secret dimensions of the cave. We do not explore these. Instead, we have come here to see a large formation of stalactites and columns.

We near the end of the giant room. Angling our lights at the ceiling of the cave reveals an enormous mass of stalactites that, individually, are larger than a person. Together they create what looks like a cascading waterfall frozen in place. At one point this cave was above the surface. Over millions of years, rainwater, slightly acidic due to absorbed carbon dioxide, percolated through the ground, gradually dissolving the limestone, leaving behind extensive underground voids and cave systems. Dripping water formed these stalactites above ground. As geologic time passed, and glaciers melted, the sea level rose and flooded the cave systems, submerging the stalactites. Now they exist frozen in time, with few visitors. We are some of these visitors. Even though I do not see my partners eyes, I know they are absorbed in this moment, too.

Just past this formation we greet our turn around point and begin to exit the cave.